Since the pronouncement of India’s No First Use Policy, which is a voluntary decision to not use one’s nuclear weapons first, two decades ago, the matter has been under constant scrutiny. The necessity, relevance and effectiveness of the approach has been a matter of discussions and deliberations ever since.

Historical Background

India’s stance on the use of nuclear weapons has slowly evolved during its 75 years of independence. From an outright opposition and demand for global and complete disarmament to acquiring nuclear capabilities to ward off the threats posed by its nuclear equipped neighbours, the evolution of India’s Nuclear Policy has been discerningly fluid.

The birth of India as a nation state was contemporaneous with the only instance of a nuclear strike by any nation on another. As a newly independent country, guided by a leadership with a strong sense of morality and righteousness, the country naturally aligned itself to a position of complete disarmament. The advocacy for a Nuclear-Weapons free world was also in consonance with Gandhiji’s ideas of ahimsa and satyagraha.

This doctrine of the Indian state, however, was called into question when hit with the reality check offered by the 1962 Sino-India war, and the subsequent nuclear tests conducted by China in 1964. These developments initiated an undercurrent amongst the Indian scientific community, with stalwarts like Homi J Bhabha making claims of possessing the capabilities to enrich the country\’s nuclear arsenal within a short span of 18 months. The official stance on the matter, however, developed rather gradually over the next decade. India refusing to sign the discriminatory Non-Proliferation Treaty and conducting its first nuclear tests (Pokhran-I) in May 1974 under the leadership of Indira Gandhi reflected the evident shift in national policy. Although it was stressed repeatedly that India had no intention of using its newly demonstrated capabilities for military purposes, the shift in position was met with opposition from major world powers and some non-nuclear nations. As a result, a new grouping, the Nuclear Suppliers Group was formed to curb the export of nuclear equipment to non-compliant countries and hence to curtail further nuclear proliferation. Even so, successive Indian governments successfully continued to ward off external pressures. The state continued to protect the nation’s nuclear option by adopting an ambiguous policy for the next two decades.

The development of nuclear capabilities by Pakistan disturbed this status quo. It was argued by the military leadership in India that the development of nuclear capabilities by Pakistan, would endanger India’s ability to assemble its conventional forces. The only counter measure, they argued, was for India to develop a nuclear arsenal as a deterrent. There was mounting pressure on the Indian state to go nuclear in the wake of the Pakistan problem. Further, in the absence of any concrete steps from the superpowers at global disarmament or even adoption of a No First Use policy, the Indian state maintained consistency in its stance and did not sign the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). It was feared that signing the treaty would result in limiting the country’s ability to safeguard its national interests and territorial sovereignty.

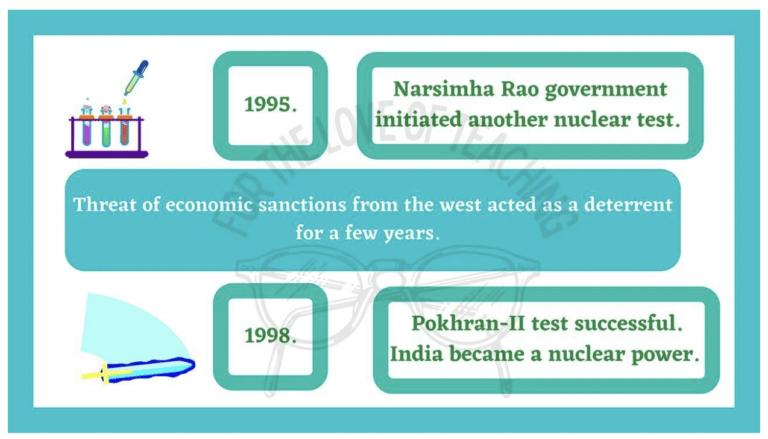

1995 saw major developments in the Indian nuclear space with the PV Narasimha government initiating preparations for another nuclear test at Pokhran. While the fear of western sanctions forced the government to forgo the initiative, the momentum it had generated would pave the way for the historic Pokhran II testing of 1998. With this penultimate step, the Vajpayee government had declared to the world that India was now a nuclear power and that the capabilities could be used for military purposes if needed. This, although not unwarranted, was undoubtedly a tectonic shift in policy and was bound to result in diplomatic fallouts, stringent economic sanctions and adversely affect potential trade deals. Further, there was a need for India to make a case for the legitimacy of its actions and to project itself as a responsible nuclear power. The No First Use Doctrine, which had been in discussion in government circles since the mid 90s gained momentum and was used as a response to the fallouts. The appendage of the doctrine to India’s Nuclear policy would help the country achieve the dual objective of safeguarding national security interests, while at the same time projecting itself as a responsible power that had the moral girth to do what global superpowers had been evading to do.

No First Use Policy

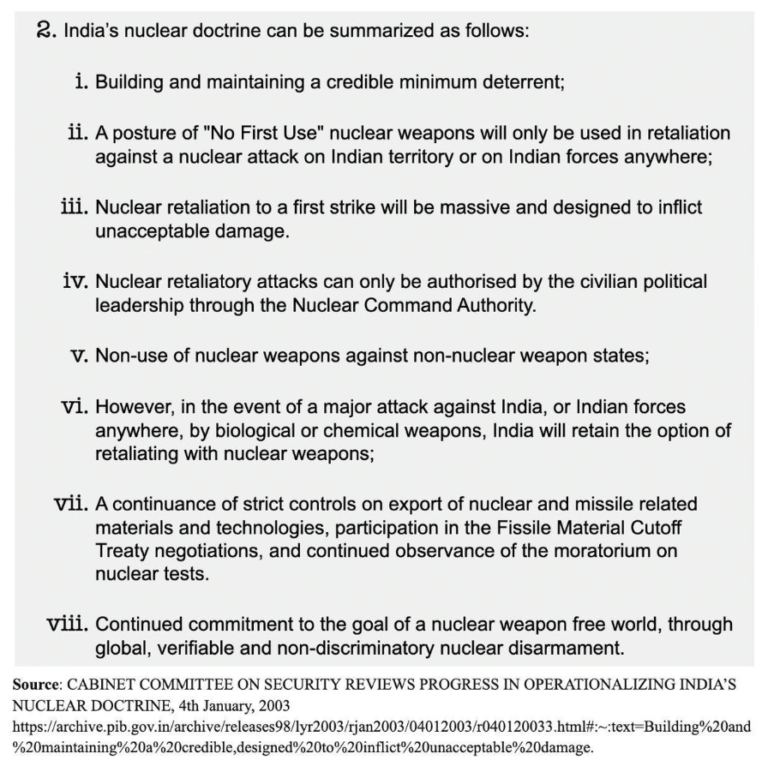

India officially adopted the “No First Use” policy as part of its nuclear doctrine in 2003. As stated in the official statement of the Cabinet Committee on Security, the nation reserves its right to use nuclear weapons in retaliation only to a nuclear attack/major biological or chemical attack on its territory or its forces anywhere. Further, it says that the retaliation to a first strike will be massive and will be intended to inflict unacceptable damages.

Literature analysis shows that for the military leadership advocating for a nuclear India, the No First Use policy was the natural logical corollary to India going nuclear. There was no scenario, according to them, where there would be a need for India to use its arsenal first. The only purpose nuclear weapons served for a country like India, which did not perceive any immediate existential threat, was of retaliatory deterrence. They further argued that as a nuclear power with significant nuclear weaponry, the country would be able to leverage its position of power to affect stability in the region by adopting a declared “No First Use Policy” along with a host of other confidence-building measures. Therefore, the policy was adopted not only as a result of political idealism but also an understanding of deep realism.

Advantages of NFU

- Projection as a responsible nuclear power.

- Addresses worries and concerns raised by fellow nuclear and non-nuclear nations and helps improve relations with them.

- It helped India sign a nuclear cooperation agreement with Japan, the only country to have faced the adverse effects of a nuclear attack.

- It was fundamental in helping India secure the historic Indo-US Nuclear deal.

- The policy, India’s track record in abiding by it, and the legitimacy it gained through the Indo-US Nuclear deal have been used as leverage by the country in its pursuit of a permanent member seat in the UN and a membership in the NSG.

- India has been trying to improve its trade ties with countries in the African Union with the aim of procuring strategic minerals like Uranium. The Pelindaba Treaty, which declares Africa as a nuclear-free zone, prohibits nuclear proliferation in the region and prevents strategic minerals of Africa from being exported freely. The Indo-US nuclear deal along with the NSG waiver it entailed has helped India achieve legitimacy to its claim of being a responsible nuclear power.

- India doesn’t need any hair triggering systems in place. And therefore, Indian nuclear arsenal isn’t a matter of as serious a concern as that of other countries.

- Less expensive than the security and safety protocols needed for first use policy.

- Practically zero chances of accidental first strikes.

Criticism

- In the presence of credible information of a nuclear attack, a No First Use policy might hinder India’s ability to ensure its security.

- There is a possibility that India’s nuclear arsenal might get destroyed in a first strike, disabling its potential for retaliation.

- Critics claim that India might not have second strike capabilities.

- Increasing nuclear “Counterforce” capabilities of adversaries poses a challenge to the NFU policy. Counterforce is when adversaries attack military installations instead of civilian cities.

- Having nuclear weapons has not deterred Pakistan from employing state sponsored terrorism and the “bleeding India with a thousand cuts” approach.

Way Forward

The No First Use Policy has been fundamental to the structuring of Indian nuclear policy and diplomacy. At the time of its development, it was perceived to be concomitant with the reasons for India mustering its Nuclear arsenal. Any evaluation for a policy change, must, therefore, analyse alterations in the Indian security scenario, if any. Also, the ramifications such a change in policy will have on diplomatic relations with other nations must also be analysed.

The only major security threat India faces from any state, continues to be from its western and northern neighbours, Pakistan and China. While both have nuclear capabilities, the developments in the past few years have altered the landscape in India’s interest.

The two major surgical strikes conducted post 2014 have significantly watered down the Pakistan threat. The actions have successfully called off the age old nuclear bluff of the Pakistani state. Further, the actions proved that there exist numerous viable conventional military measures for exhaustion before a nuclear option is considered.

While, the threat posed by China has increased substantially in the last few years, reaching its peak during the 2020 Galwan clashes, the war posturing that has followed and the intermittent news reports of possible incursions into Indian mainland, the threat of a nuclear attack is not yet evident. India has long taken solace in the Chinese No First Use policy. The future of the Chinese policy will have serious repercussions for India. The omission of the NFU policy from the Chinese 2013 defense white paper, had sent serious shock waves across the Indian strategic community. Although the 2019 Chinese defense white paper reaffirmed their commitment to the NFU, the actions of the Chinese in Galwan and other regions across the LAC, which threw to the wind multiple bilateral agreements and confidence building measures, have diminished India’s confidence in the Chinese.

As has been discussed, the No First Use clause in India’s nuclear policy has helped it position itself as a responsible nuclear power. Indian diplomacy has successfully milked this to gain major diplomatic points. From the Indo-US Nuclear deal, to improving relations with other major countries including signing of a nuclear cooperation agreement with Japan, all these major achievements have been made possible by the existence of the clause. In the event of a policy reversal, the existing treaties, waivers and strides in relationships might face existential threats. Unless the security threat faced by India is significant enough, it would be an incredibly arduous task to convince partner nations of the legitimacy of the policy change.

It is undeniable that the Indian security scenario has evolved in the 2 decades since the official adoption of the No First Use policy. But, have they been significant enough for a complete reversal of the state’s nuclear policy? The question definitely demands serious strategic perusal, whose conclusions will have ramifications on the future of India, its neighbourhood and global geopolitics.

References

“Nuclear India: A Short History.” Transnational Institute, www.tni.org, 1 May 2006, https://www.tni.org/es/node/8050.

Evolution of India’s Nuclear Policy. Government of India, 12 Jan. 2010.

Rajgopalan, Rajesh. “The Strategic Logic of the No First Use Nuclear Doctrine.” Observer Research Foundation, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/strategic-logic-no-first-use-nuclear-doctrine-54911/. Accessed 30 July 2022.

Vineet. “No First Use Policy: A Viable Perspective? – RGNUL Student Research Review (RSRR).” RGNUL Student Research Review (RSRR), rsrr.in, 4 Jan. 2020, http://rsrr.in/2020/01/04/no-first-use-policy-a-viable-perspective/.

“India’s No-First-Use Dilemma: Strategic Consistency or Ambiguity towards China and Pakistan | SIPRI.” India’s No-First-Use Dilemma: Strategic Consistency or Ambiguity towards China and Pakistan | SIPRI, www.sipri.org, 2 Dec. 2020, https://www.sipri.org/commentary/blog/2020/indias-no-first-use-dilemma-strategic-consistency-or-ambiguity-towards-china-and-pakistan.

Kumar, Sundaram, and M. V. Ramana. “ India and the Policy of No First Use of Nuclear Weapons,.” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2018.1438737.