Children of prisoners are an extremely vulnerable yet severely ignored group. It was only recently in 2005 that they were included in the category of ‘children in especially difficult circumstances’ in the National Plan of Action for Children (NPAC). Often, they are aptly referred to as the ‘forgotten victims of crime’ and the ‘Cinderella of penology’

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Child Act states that a child is “any human being under the age of eighteen, unless the age of majority is attained earlier under national legislation.” The upper limit has been specified to be 18 years with the only exception being in nation-states where majority is said to be attained earlier by law. The Indian Majority Act, 1875 states that all permanent residents of India attain majority at 18 years of age. In this article, ‘children’ will be used to refer to individuals who fit the criteria of above-mentioned definition and find themselves in the following circumstances:

(a) Children living in prison with their mothers

(b) Children living in state institutions or foster care while their mother serves her sentence (c) Children living with members of their family or friends while their mother serves her sentence

(d) Children born inside prison

In India, a woman prisoner (undertrial/un-convicted or convicted) is legally allowed to bring her child upto the age of 6 years into jail with her. The Prison Statistics report published periodically by the NCRB (National Crime Records Bureau) states that, as of 31st December, 2021 – there are 1,427 women prisoners in India. They have a total of 1,628 children dependent on them. Most

women are convicted for murder. In cases where the spouse is not present and/or the children do not have anyone to take care of them, they accompany their mother to prison.

In this article however, we will be focusing on female inmates and their dependents living in Maharashtra. A single state has been chosen since prisons come under jurisdiction of the state, so the rules governing them differ from state to state.

While it is widely accepted now that prisons are meant to be places that induce a positive transformation in prisoners, this was not the perspective held earlier. Macaulay, who wrote the IPC, held the belief that for prison systems to be effective, they had to inflict maximum punishment. All humanitarian and reform needs were discarded and a machinery to impose maximum punishment was designed. The contemporary prison administration is a legacy of British rule.

Children who grow up within this system are exposed to a certain amount of neglect, trauma and abuse. Traumatic experiences during early developmental years have a lasting impact on children. This is exceptionally detrimental for children from the ages 6 to 12 as an individual’s personality gets molded during these years. Incidents like parents getting arrested in front of children leaves a lasting impression on the child. It causes a significant amount of psychosocial damage, with the children having flashbacks of the incident. It is thus, the responsibility of every adult involved to reduce the negative impact the arrest may have on any children involved. Most females report a lack of sensitivity displayed by the prison officials during the time of their arrest. They describe being dragged by their hair out of their house while the confused child cries inconsolably. In most cases, the mother is not informed of the provisions set up to take care of children. The child is left alone, unaware of their mother’s plight and without food and water. Research has shown that separation from the mother even for one-week has a negative impact on children. These incidents can be characterized as Adverse Childhood Experiences or ACEs. The toxic stress generated by Adverse Childhood Experiences has the capacity to change the structure of a child’s brain and thus become a part of the child’s biology. Keeping in mind the adverse effects of ACEs, the trauma, neglect and abuse children of incarcerated parents experience manifests as:

(1) behavioral problems like aggression

(2) educational issues like grade repetition

(3) health issues like physical ailments, depression and PTSD

(4) social issues like homelessness due to an inability to pay rent, food insecurity and (5) stigma from friends, neighbors and schools.

Their circumstances force them to fend for themselves. More often than not they get involved in anti-social activities. The following account of a female prisoner, collected by a Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) project named Prayas, illustrates this point well.

Savita, a mother of 3 children is serving a sentence of 16 years for killing her husband. Her spouse used to molest her 13-year-old daughter. She had reached out to her in-laws regarding this issue but they refused to believe her. One day she caught her husband red-handed. She flew into a rage and chose to end his life. While she serves her sentence in prison, her daughter being the oldest has become responsible for her siblings. She has entered into a relationship with a 50- year-old man who gives her money from time to time.

In this manner, children end up becoming secondary victims. In order to prevent this from happening and to protect the children of India, there is an urgent need to study and understand their situation.

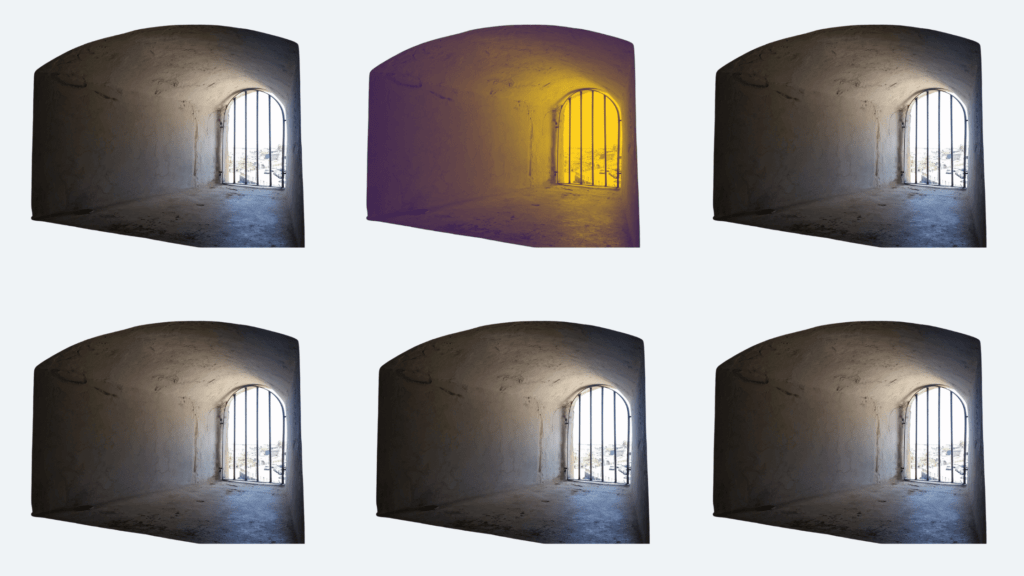

The state of Maharashtra has a total of 60 prisons. However only one of them has been designed to house women, Byculla women’s prison. Since women only form 4% of the prison population, it is considered economically inviable to invest in infrastructure for women. An alternative solution is enforced wherein female prisoners are often placed in small, confined enclosures within male jails. Due to this severe lack of infrastructure, women who have committed petty crimes like pickpocketing end up in high security prisons.

Thus, women and their dependents live together in one relatively smaller, heavily guarded enclosure. Living in an overcrowded cell leads to heated arguments between the mother and her children and amongst the children. The environment of a prison is an aggressive one, fraught with profanity. While fleeting swear words do not cause any harm to children, expletives used as a substitute for physical aggression are harmful. This is because it takes on the cloak of verbal abuse and harassment. In addition to psychological strain, overcrowding worsens hygiene conditions. Small infections spread easily. The consequences of overcrowding were acutely felt during the Covid-19 pandemic. Even though the National Prison Manual prescribes a segregation of cells to prevent infections from spreading, the reality is far from different. While claims of precautions and utmost care were being made by the Maharashtra home and prison departments, cases inside prison were on a rise.

Even when overcrowding is not an issue, the accommodations provided are found to be inadequate. A report published by the Ministry of Women and Child Development in June 2018 stated a lack of beds, washrooms, toiletries and unsatisfactory heating/cooling arrangements in cells. The National Prison Manual states nutritional norms for children, pregnant and lactating mothers. However, the special diet usually amounts to an extra glass of milk. In the worst-case scenario, breakfasts happen at 7 AM which is then followed by lunch between 7 and 8 AM. Inmates are then, forced to preserve food to eat when they are hungry for themselves and their kids.5

For children born and/or living in prison, their socialization is gravely affected. Their only exposure to male figures are the authoritative police and prison officials. It has been observed that young boys living in prison end up imitating female mannerisms and referring to themselves as a female. They are not aware of a concept of home like children living outside are. Moreover, seemingly normal sights like a stray dog are so unfamiliar and novel to them, that their response to strays is fear.

The need for reform was acutely felt during the Covid-19 pandemic. On March 31st, 2020 the Byculla prison had 352 prisoners against its actual capacity of 200 prisoners. This translates to an occupancy rate of 176%. A major cause of concern were the 26 children present in prison with their mothers. By no fault of their own, these children found themselves in an undesirable situation. Studies conducted by TISS have concluded that the prison is not a conducive place for children to live. The outbreak of the virus exacerbated the issue. The process of decongestion was initiated during the pandemic. Undertrial inmates were let out on bail and women and children were moved into separate enclosures to curb the spread of the virus.

In addition to decongestion, the Byculla female prison has implemented something crucial. 26 children live inside the walls of this prison. In 2019, it was announced that an unused patch of land would be converted to a playpen! It would not include standard toys like balls and whistles. Instead, equipment that would encourage divergent thinking like plywood boxes with games painted on them which can also be used as tunnels, swings in the form of jute tires, a blackboard where kids can showcase their art and many more.All toys put in are multi-functional and cannot be used as weapons by inmates. This playpen is being built with the aim of encouraging and providing mothers ways to spend more time with their children. It was born after many discussions with prison officials, a TISS project named Prayas and Balaji Foundation.

Prayas, a Tata Institute of Social Sciences has been doing tremendous work for the children of incarcerated parents. It was born out of a chance encounter between one girl whose parents were serving a sentence for murder, with a student pursuing her Master’s at TISS in Social Work named Krupa Shah. This project works on criminal justice mainly in Maharashtra. With the efforts of TISS, anagwadis or creches have been set up in eight prisons across the state.

Children living separately from their mother, outside prison often lose touch, only meeting each other once a year or less. Since there is no dedicated agency that looks after the needs of these children, information about their children is not known to incarcerated mothers. When they do meet, a role-reversal occurs wherein the child comforts the mother about the situation at home. With their advocacy efforts, Prayas was able to get a circular issued through the Department of Prisons, allowing mothers and children to talk on the telephone. In 2018, inmates were allowed to interact with their children through a video call for 5 minutes for the cost of 5 rupees.

Realizing the need to keep prisoners connected to the outside world to keep them from returning, the Maharashtra State Prison Department decided to introduce an initiative called Galabhet. Through this programme, children were allowed to meet their parents once a quarter. The outcome of this programme was assessed in collaboration with Prayas. Data was collected from five prisons and the results were positve. Inmates reported better mental health and felt more hopeful for life forward.

While a significant amount of work is being done, there is scope for improvement.

For starters, most female inmates are not aware of their rights. As suggested by a project director at Prayas, it should be made compulsory for the arresting officer to –

(a) Ask if the individual has children

(b) Let the mother know that she can take her children upto 6 years old into prison with her. In order to mitigate the gap between mothers and her kin, a representative who keeps in touch with the children living separately from their mother, regularly updates the mother and ensures that they meet would be incredibly advantageous. It would reduce the toxic stress generated in children when they stay away from their mothers whilst preventing isolation of the inmates. This will go a long way in averting both of them from getting involved in anti-social activities. Inmates who have children must be considered to be lodged in an open jail. In this system, the restrictions are less stringent and families can come spend nights with inmates.

In conclusion, the deficiencies of the system are turning children into secondary victims. An urgent need for intervention is felt for inmates and their children. Very often the conditions a female inmate and her children find themselves in, depends on the mercy of the police officer-in charge. This occurs due to a huge gap between policy and implementation.