The effectiveness of foreign aid on a country’s development has been a subject for debate for quite some time. While there is empirical evidence available that supports the claim that foreign aid leads to growth, there is also mounting literature on how aid has not worked in several cases. It is important to understand whether the recipient countries’ ownership of reforms is necessary for aid to be successful. Moreover, if this is the case, why do other variables like institutions of recipient countries and more not play a role in determining aid effectiveness?

Literature Review

Firstly, some scholars believe that foreign aid has a positive impact on the economic growth of a country. It increases the domestic resources and supplements the domestic savings which allows the country to invest in infrastructure, technology and access to foreign markets (Aryeetey & Cox 83; Tsikata 89). The trends of Official Development Assistance (ODA) to Africa from 1960-2002 have indicated that aid does have a correlation with economic growth and poverty reduction (Pallage & Robe 2).

Others claim that there is a negative correlation between economic growth and foreign aid. For instance, some argue that in the case of Ghana, corruption and the high interests on the loan payments ended up harming the economy. They claim that for foreign aid to work, it needs to be diverted towards capital formation and the development of labour through training since both of them are positively related to growth (Konadu et al. 259).

The third strand argues that aid cannot lead to development without a proper institutional structure in the recipient country. If it does not have efficient institutions that perform tasks like collecting taxes, then it is not possible for the country to substitute the aid received with domestic revenue and it becomes completely dependent on aid (Mbaku 103).

Lastly, foreign aid only works if there is a sound policy environment to utilise the aid for the implementation of projects that lead to economic growth or the development of human indicators. A recipient country which does not create a suitable environment that supports production, regulates aid and curbs corruption and ensures that the positive effects are being diversified would not experience any sustainable development (Tawiah et al. 25).

Case Study: Ghana and Angola

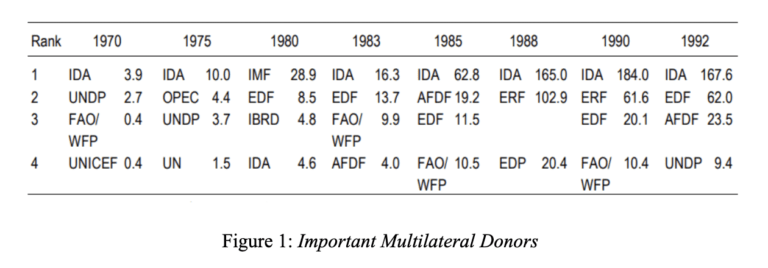

Ghana and Angola share a colonial history, even though Ghana gained independence much earlier and Angola was torn due to a civil war for almost thirty years after independence. While Angola was in the middle of a civil war, Ghana has witnessed several regime changes, from military dictatorships to democratic governments. Ghana received aid starting in the 1970s, mainly from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF). Angola, on the other hand, started receiving aid in the 21st century from China, a feature of South-South cooperation.

- Aid Strategy

Ghana – foreign aid to Ghana can be divided into two phases. Firstly, the Economic Recovery Programme (ERP) was carried out by the World Bank and IMF in 1983. This programme primarily aimed at strengthening the Ghanian economy by increasing production of goods, stabilising inflation and improving the balance of payments of the government. Other goals were to build social infrastructure and reduce illegal trade (black market and smuggling). Secondly, the ERP-II in 1986 focused on deeper issues like sustaining GDP growth, improving efficiency of the public sector as well as the well-being of the underprivileged (Tsikata 74)

Angola – China has redefined the way foreign aid is given through Angola. It invests in infrastructure projects i.e. Angola’s post-war reconstruction is undertaken by Chinese companies that are recommended by the Chinese government. A multisectoral group, Gabinete de apoio técnico de gestão da linha de crédito da China (GAT) ensures that the projects are being implemented and Angolan ministries are responsible for keeping track of the progress and ensuring that proper training is being provided to workers (Aberg 42). This means that China dominates the coordination of policy in Angola.

For China, the repayment for such aid is done in oil. Angola repays only after a specific project has been completed and the oil revenue is deducted from the existing debt (Aberg 43).

However, aid also contributes to the construction of hospitals, educational programs and scholarships.

- Economic Growth

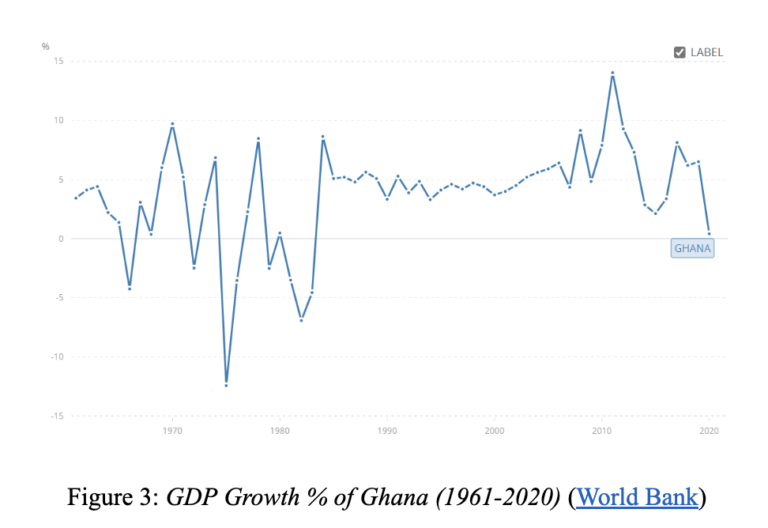

Ghana – the ERP had positive results on the economic growth of Ghana. Policies like increasing cocoa producer prices by 67%, eradicating price controls on products like maize and privatising state-owned enterprises prevented a major economic crash (Thomson 195).

The stabilisation process can be seen in the GDP growth of the economy. The GDP increased from USD 4.06 billion in 1983 to 4.41 billion in 1984. Moreover, there were no major crashes like in the pre-1982 period which indicates that the reforms were sustainable and had a positive impact in the long run.

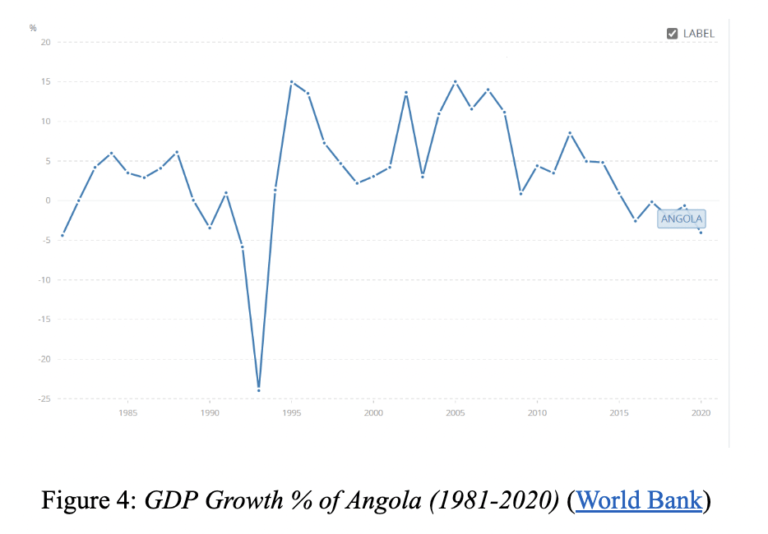

Angola – the kind of projects that China has undertaken have not been proposed by other OECD-countries. The infrastructure projects have certainly helped in establishing an economic base that can be developed over a period. Eximbank has also given USD 203 million to increase Angola’s agricultural production through machinery and effective irrigation systems (Aberg 55). Given that the whole process of aid is based on Angola repaying its debt through oil revenue and petroleum has the largest share in the Angolan economy, a positive relation between crude oil exports and GDP can be seen (Begu et al. 11).

While an upward trend can be seen after the first Chinese investment of USD 2 billion in 2004, the trend is not consistent. Even though the decline after 2008 can be attributed to the 2008 financial crisis, the economy has been growing at a diminishing rate after 2012.

- Poverty/Human Infrastructure

Ghana – according to the World Bank, the incidence of poverty fell between 1987 and 1990 due to sectoral policy reforms which led to agricultural production and redistributed wealth (17). Poverty increased in two years but after transitioning back to a democracy in 1992, the poverty rate started decreasing. This indicates that aid was indirectly successful in creating a suitable policy environment for poverty alleviation.

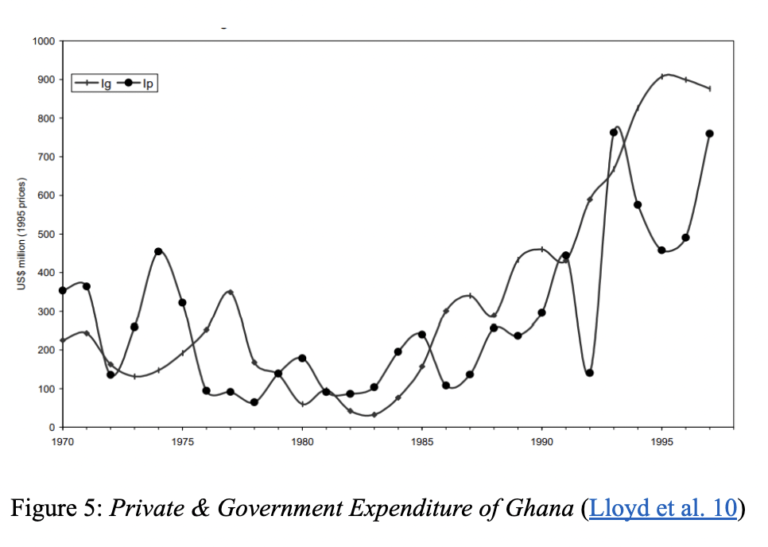

Another aspect that can be looked at for human infrastructure is government investment which is crucial for the development of education, healthcare and more. It is clear that in the post-1983 period aid encouraged an increase in government investment.

Donors are also involved in education and healthcare programs. For instance, the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) started a program called ‘School for Life’ which supported 70,000 children to stay in primary school and funded NGOs that work towards girls’ education, malaria eradication and more (Boye 39). There is no clear correlation between aid and development of human infrastructure. Ghana’s school enrolment percentage in primary schools was volatile from 1980-2002 and started increasing after this period. While the life expectancy has increased, it is still quite low and it is difficult to link this development with foreign aid.

Angola – the 2021 Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) reported that 32.5% of the Angolan population lives under severe multidimensional poverty (UNDP 29). When it comes to poverty reduction and foreign aid, no clear correlation can be made yet. There is insufficient evidence to claim that foreign aid affected poverty alleviation. However, a holistic indicator of development like the Human Development Index (HDI) has a positive correlation with the export of crude oil to China, even though the growth of HDI is at a slower pace (Begu et al. 12). The data for school enrolment percentage is missing for many years and while life expectancy has been rising slowly, it is difficult to link it to Chinese foreign aid.

There are very few Angolans hired and that, too, for menial jobs. Thus, Chinese aid has a major disadvantage on the development of skills amongst the Angolan workforce.

Foreign Aid and Recipient Country’s Ownership

The case study shows that the two aid strategies differ in the recipient country’s involvement as well as the extent of flexibility provided by the donor. China is directly involved at the policy level due to the infrastructure projects in Angola. On the other hand, the World Bank and IMF only gave financial assistance and policy directions in Ghana. Moreover, while both countries experienced economic growth, the growth was only sustainable in Ghana. Chinese motives for acquiring oil are clear in Angola but it is difficult to gauge western interests in Ghana besides assisting development. The Chinese enterprises, by not hiring Angolan nationals, do not contribute to the human infrastructure. There is insufficient evidence to correlate Chinese aid and poverty reduction in Angola but Ghana has recorded significant poverty reduction ever since 1992. Moreover, there is a clear correlation between aid effectiveness and the level of corruption in the country. While Ghana and Angola both record high corruption when compared to international standards, Ghana still ranks much higher than Angola. This shows that Chinese aid has not been effective in curbing corruption.

Conclusion

Foreign aid reached an all-time high in 2020 reaching USD 161.2 billion (OECD). Therefore, foreign aid has been a crucial element for the development of the least developed as well as developing countries. It is important to evaluate the impact that foreign aid has had on recipient countries. If, for instance, large sums of money are not reaching its destination during reforms due to corruption, then these factors need to be recorded and worked upon by donors and international organisations in their conditionalities.

References

-

- Aryeetey, Ernest, Aidan Cox. Foreign Aid in Africa: Learning from Country Experiences. The Journal of Modern African Studies, Edited by Jerker Carlsson, Gloria Somolekae and Nicolas van de Walle, 1997, pp. 65-111.

- Pallage, Stéphane, and Michel A. Robe. “Foreign aid and the business cycle.” Review of International Economics 9.4, 2001, pp 641-672.

- Appiah-Konadu, Paul, et al. “The effect of foreign aid on economic growth in Ghana.” African Journal of Economic Review, 4.2, 2016, pp 248-261.

- Mbaku, John Mukum. Institutions and development in Africa. Africa World Press, 2004.

- Tawiah, Vincent Konadu, et al. “Political regimes and foreign aid effectiveness in Ghana.” International Journal of Development Issues, 2019.

- Tsikata, Yvonne M. Aid and reform in Africa: Lessons from ten case studies. World Bank Publications, Edited by Devarajan, Shantayanan, David Dollar, and Torgny Holmgren, 2001, pp 45-100.

- Åberg, John. “Chinese Financial Assistance in Angola-Promise, Curse or an Uncertain Venture?.” 2010.

- Thomson, Alex. An introduction to African Politics. Routledge, 2010.

- Begu, Liviu Stelian, et al. “China-Angola Investment Model.” Sustainability, 10.8, 2018, pp 2936.

- Ghana Poverty Assessment. World Bank, November 2020.

- Lloyd, Tim et al. “Aid, Export and Growth in Ghana”, CREDIT Research Paper No. 01/01, 2001.

- Boye, Ruth Adjeley. “Impact of Foreign AID on Poverty Reduction in Ghana (2008-2018)”. Diss, University of Ghana, 2019.

- UNDP. Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2021: Unmasking disparities by ethnicity, caste and gender. 2020.