Every evening, hordes of office workers descend from their skyscraper worlds of financial models and powerpoints onto the bustling streets of Lower Parel to satisfy their culinary cravings. The choices at their disposal are ample. Established in 1920, Shree Datta Boarding House has been offering its signature home-style Malvani cuisine to hundreds of hungry clamouring souls everyday — from the blue-collar workers who slogged in Parel’s now defunct textile mills to the white-collar young professionals and executives plying their trade in the towering glass buildings that have now replaced them. Underlying this fast-changing structural and demographic reality of the region is the long-debated phenomenon of gentrification — an urban transformation with deep social, economic and political implications. With the population in its cities estimated to cross 800 million by 2030, India is at the cusp of an urban revolution that will be significantly shaped by these stories of disparity, development and gentrifying skylines. In between the humid hummings of age-old outlets like Shree Datta Boarding and the plush interiors of the newest cafe in Parel’s high streets, this piece will seek to understand the manifestations of gentrification in the Indian context and its growing relevance for policymakers in crafting ‘successful’ urbanisation.

A Beginners Guide to Gentrifying Neighbourhoods

In much of the early literature on the topic, gentrification has been defined as a transformational process of a neighbourhood wherein new affluent households displace the existing low-income residents of the place. Neil Smith’s influential work on the Rent-gap theory describes the spatial economics of how this transformation comes about. He argues that when a neighbourhood “undergoes deterioration”, as was the case with Parel’s dilapidating chawls post deindustrialisation, there is a corresponding fall in rents in the area. This leads to a growing gap between the current rent and the ‘optimum’ rent that can be earned when the land is put to its best possible use. Once the gap is wide enough, real estate developers and other agents with vested interests in the potential profit to be “gleaned” from redevelopment bless the neighbourhood with new investment.

As understanding of gentrification evolved, its definition expanded to include the marked changes in visual features of the region as well as the impact on the cultural and demographic makeup of the neighbourhood. To understand the huge fuss about a bunch of young people with money moving into such localities, let us break down the advantages and problems this ‘hipster’ invasion has.

If you were to take the standard metric of per capita incomes, the positive impacts of gentrification are undeniable. It brings about investment in neighbourhoods that have endured long periods of neglect. Local businesses benefit from having more customers, and that too people with high disposable incomes. And say what you will about their bohemian lifestyles, the trendy cafés and quirky shops that open up in wake of this new demographic generates valuable sources of employment vis-à-vis incomes for the locals.

More generally, these gentrifiers come with certain high expectations of the quality of public services they should receive. Stuart Butler of the Brookings Institution argues that these young professionals make a ‘fuss’ and put pressure on public institutions for improvement in schools, the police and the city infrastructure at large, thereby also having positive spillover effects for the low-income locals.

A Woke Narrative Against Urban Prosperity?

If gentrification has all these substantially positive effects then why are we even concerned about it? Let it continue, even encourage it, you might say. You would not be alone in this thought. In fact, a 2018 article in The Economist magazine went so far as to say that gentrification is an “urban myth” — backed with a barrage of economically sound reasons as to why the phenomenon is actually symptomatic of economic progress.

However, before blindly conflating gentrification with urban prosperity, it is important that we locate the issue in the Indian context (using the case study of Lower Parel) to understand the drawbacks and relevancy of certain advantages mentioned above.

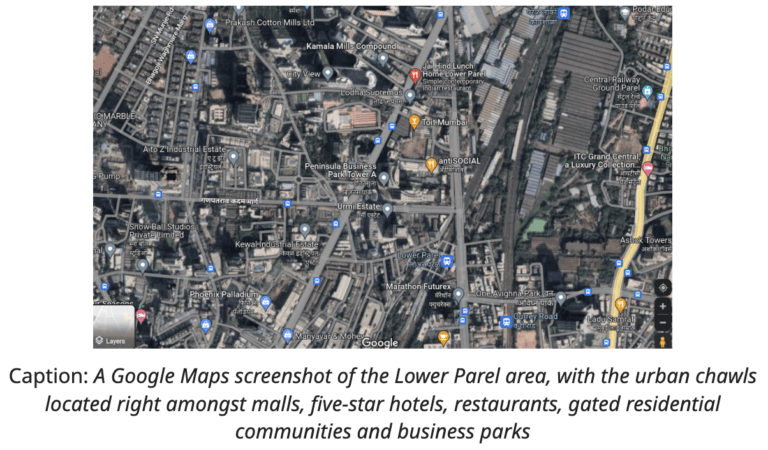

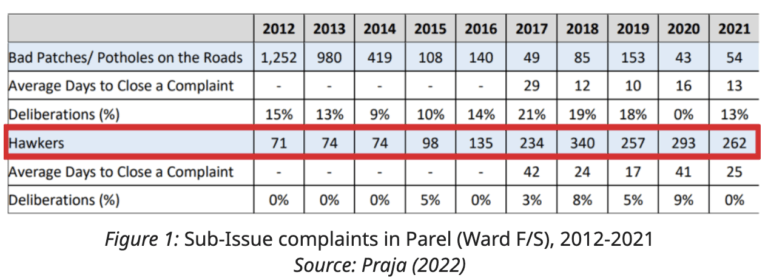

For instance, the influx of affluent families to the region has led to the formation of many gated communities. While it could be argued that gentrification leads to a decrease in economic segregation and an increase in social mixing, the reality is quite starkly opposite. Amidst the juxtaposition of the residential high rises and the dilapidated chawls right below their windows, the existence of an “invisible wall” seems to shape the region’s social fabric. For the gentry residing in the glass towers, the chawls are nothing more than an eyesore — a hindrance to their “heightened fantasies of contemporary global urbanity”. Indeed, efforts have been made to reclaim these areas from the urban poor; seen in a growing intolerance of the informal markets that proliferate on the shared streets below. As seen in Figure 1, there has been a steep rise in the number of cases being reported in Lower Parel’s ward against hawkers and street vendors over the past decade.

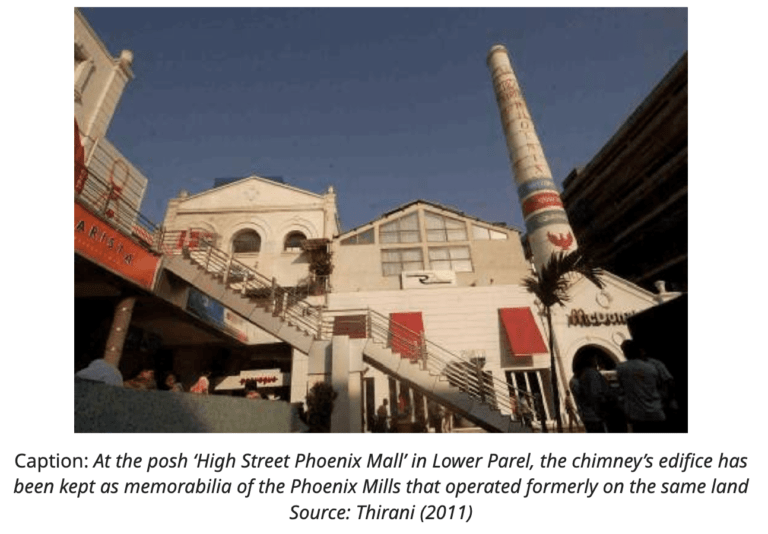

Aided by institutions of the state and municipalities, the mass demolition drives that accompany the gentrification process are often masked under narratives of urban development and ‘rejuvenation’. However, what these city beautification drives fail to consider is that the redeveloped infrastructure will be biased towards use by the elite and upper-middle classes. The ‘bourgeois environmentalism’, as coined by Amita Baviskar, that this new money demographic partakes in marginalizes lower income groups and is inherently exclusionary of their aspirations and ways of living.

Moreover, growing alienation from their communities and resentment towards the inevitability of their evictions is compounded by soaring costs of living for the residents of these chawls. For those living at the margins, these pressures have been exacerbated by the growing insecurity of their livelihoods. With the closure of the mills and substitution of the manufacturing industry by the service sector, labourers are now forced to work as vegetable vendors, drivers or as delivery partners for app-based services, delivering orders to the very high-rises that displaced them.

‘Urbanisation as Opportunity’: Crafting inclusive growth stories

Given the spatial and socio-economic context of this ‘desi’ gentrification, it is important to place our study in the larger framework of economic growth to understand its significance. Why should macroeconomists and policymakers concern themselves with the opening of a Starbucks in Lower Parel? The answer lies in deconstructing Romer’s work on urbanisation and its implications for the growth story of developing countries like India.

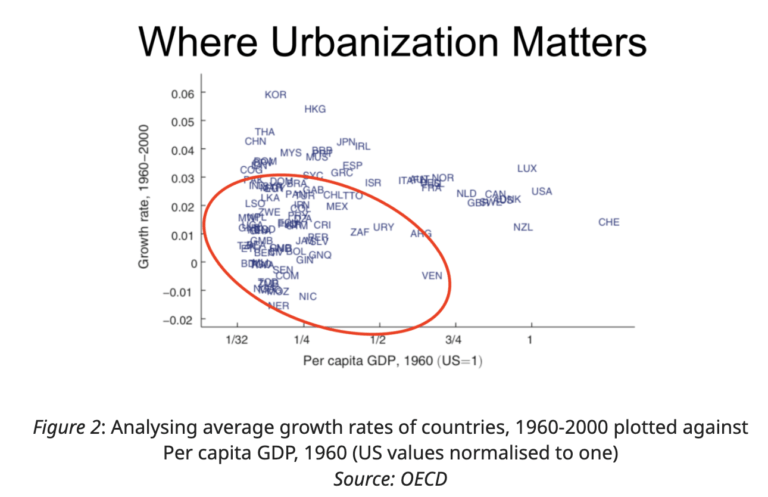

Romer argues that for much of the developing world, especially countries like India whose economy is yet to peak, urbanisation presents a golden opportunity for augmenting “catch-up” growth (see Figure 2). In his 2018 Nobel prize winning lecture, he echoes Edward Glaeser in emphasising how cities give opportunities for people to gain the “benefits of interactions with other people”. The links between economic prosperity and urbanisation have been made explicit by several academics. Alfred Marshall’s seminal claims on dense agglomerations facilitating the flow of ideas were validated by Feldman and Audretsch’s empirical findings of innovation being concentrated in urban areas. The evidence is overwhelming — cities make us smarter.

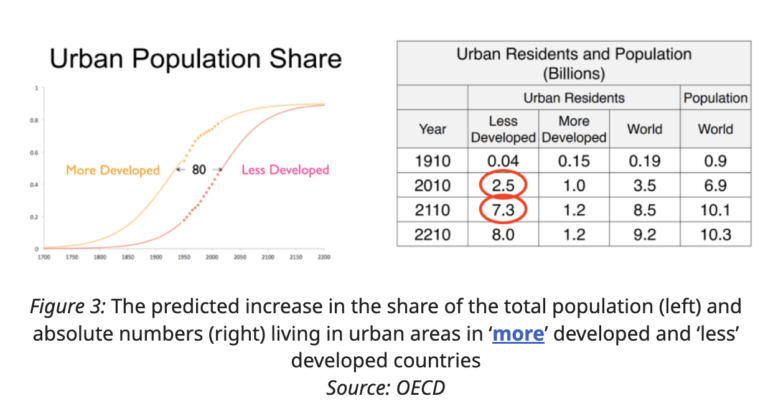

With the amenities and opportunities that cities offer, the urban share of the population, as well as absolute population, is predicted to increase exponentially (see Figure 3). Accommodating this boom in sync with economic growth will require prompt and practical policy responses. Indeed, what policymakers have now at their hands is an incredible opportunity to successfully plan the expansion and redevelopment of urban spaces. But why the urgency? If we were to consider a critical 2016 report on the issue, the cost of failure (read: imprudent urban planning) is too high — an estimated cost to India’s development of up to US $1.8 trillion per year by 2050, or nearly 6% of the country’s GDP.

This is where gentrification comes in. As witnessed in the metamorphosis of Lower Parel, rapid gentrification compounded by poor urban policies and infrastructural planning have led to multiple disasters in the region in recent years. In 2017, 22 lives were lost in a stampede at Elphinstone Road railway station. A fire in a Kamala Mills pub aggravated by haphazard structures and poor safety measures claimed 14 lives. These tragedies, as well as the daily travails of people like traffic congestion, all point to a gentrification process that has excluded consideration of the booming population. At the fringes, change is costly, often fatal.

Conclusion

In the spatial context of the developing world and as seen in our case study of Lower Parel, urbanisation, and thereby gentrification, are inevitable. The problem now is that when new people and money flow into city neighbourhoods, the existing low-income population seldom benefit from it. Urban development has been on the backburner of the government’s economic plans for far too long, and inclusivity has largely been mutually exclusive to growth in these conversations.

Just a short walk away from the international-chain restaurants, multi-storey car parks, and the high-speed elevators in the high-rise business offices, you arrive at Lower Parel’s Currey Road railway station with its rundown foot-over-bridges — no escalator or elevator in sight. Civic infrastructure has barely kept up with private investment. It is crucial, now more than ever, that policymakers craft sustainable, inclusive and equitable urban policies that benefit the gentrifiers and their demand for urban aesthetics as much as they do local communities; for it will define our growth stories for years to come.