Abstract

In December 2022 the unemployment rate reached a record high at 9 percent, which is the highest it has been since the pandemic. India currently enjoys a demographic dividend where almost 65 percent are under the age of 35. However, despite having a young population, the labour force over the years has decreased. Enrolments at every level of education have improved, however with increase in educated youth, there has been a shortage of jobs to employ the educated labour force. The number of jobs created in the manufacturing sector and agriculture have reduced significantly, whereas the jobs created in the services sector have seen a steady increase over the years. Around 90% of the jobs created in the non farm sector are informal with no social security. With the current unemployment crisis reaching its peak recently, it is important to analyse some of the ongoing employment and unemployment trends in order to understand why unemployment rates have been increasing. The article, hence, would be looking into the employment and unemployment trends over the past ten years with a special emphasis on youth employment and unemployment. Further the article would be looking into sectoral distribution of employment and unemployment and possible solutions to improve unemployment will be looked into.

Introduction

India has a distinct advantage in the labour market compared to most developed and less developed countries due to the fast changing age distribution of population (Kundu, 2013). As a consequence of decreasing population growth, the working population, i.e, aged between 15-59 has increased and will continue to do so for the next few decades. In the recent years, India has displayed commendable strides in terms of economic growth, however it has not been followed up by increase in employment rates. This phenomena is termed as jobless growth and India is a perfect example of it. The Indian economy is passing through an unprecedented phase in its employment history, in which total employment is declining, and open unemployed and disheartened Not-in-Labour Force- Education-Training” (NLET) youth (a reserve army) are rising massively (Mehrotra & Parida, 2019) .

The total employment from 2011-12 to 2017-18 declined by 9 million along with that concerns regarding low growth productivity and lack of decent jobs are some of the challenges faced by the policymakers. Over the years there has been a sharp increase in the enrolment rates at every level of education and it was expected that this would lead to better employment rates. However, this leads to creating demand for high skilled level jobs in the services and the manufacturing sector as the labour force started to opt out from the agricultural sector. This structural shift of decline in employment in agriculture is actually good as it leads to employment into more productive sectors which helps boost the economy. However, not being able to create decent employment in the non farm sector is still what is of concern.

Unemployment recently reached an all time high at 9 percent in December 2022, which is the highest it has ever been since the pandemic. Youth unemployment is what is concerning, as the labour force (those working and looking for work) has been steadily declining which clearly means that there has been a lack in creating jobs and the demand for work has reduced significantly.

Employment and Unemployment Trends from 2010-11 to 2021-2022

In this section we will specifically be looking into the employment and unemployment trends over the past ten years, while specifically emphasizing on the youth employment and unemployment trends.

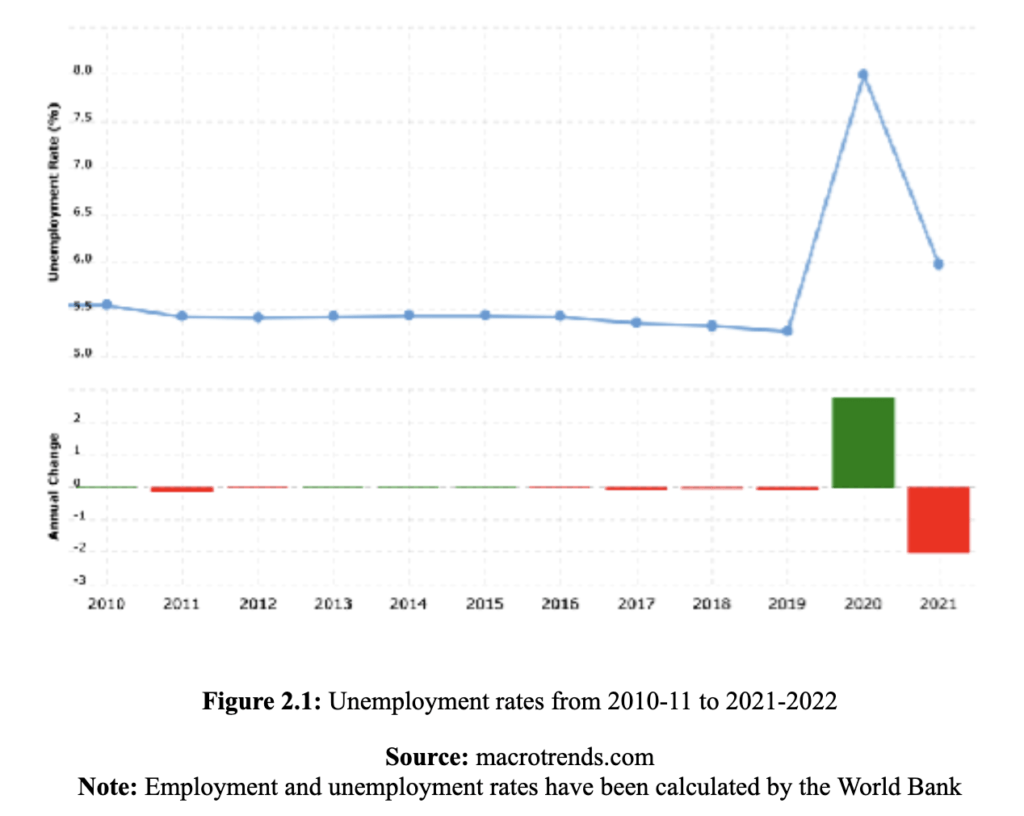

Looking at Figure 2.1, it can be seen that the unemployment rates it can be seen that unemployment rate was at 5.5 % in 2010-11 and has been around the same rate till 2019-20. However, during the pandemic, unemployment rose to 8% and came down to 6% in 2021-22. However, the unemployment rate rose to 9% in December 2022.

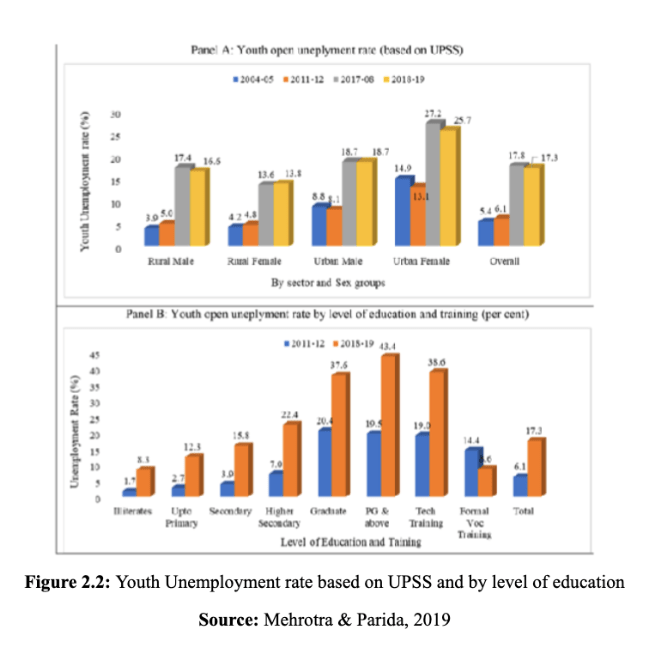

The youth population has been rising, which makes a larger percentage of population in the working age bracket, however this hasn’t been reflected by an increase in the labour force. Looking at Figure 2.2 given below, it can be seen that the open youth unemployment rate has increased to 17.3% in 2018-19 from 6.1% in 2011-12. In fact what is even more worrying is that the youth unemployment rate amongst the graduates has increased from 20.4% in 2011-12 to 37.6% in 2018-19. According to Mehrotra and Parida in their paper, India cannot take advantage of its demographic dividend if those entering working age either don’t look for work or don’t find work. In order to take advantage of the dividend it is important that the youth be employed in the non-farm sector. This is because productivity in industry and services is higher than in agriculture. Female unemployment has also been decreasing from 2011-12 to 2017-18. Even though there has been a significant shift in females opting out of agriculture, they haven’t been able to integrate into the labour market in the services and manufacturing sector. Lack of jobs created for women, more women opting for higher education and cultural factors which do restrict women to participate in the labour market are some of the factors responsible for unemployment among females.

It can be seen in Figure 2.2, that female unemployment both in rural and urban females have increased. In fact, with increasing levels of education, the unemployment rates have also increased. A huge contrast can also be seen in the unemployment rates amongst rural and urban females suggesting that more urban females are opting to be out of the workforce. Amongst men as well, a difference can be seen between rural and urban males, where there is 16.6% unemployment in 2018-19 whereas it is about 18.7% in urban male. Scarcity of non-farm jobs and rising open unemployment together have resulted in a massive increase of disheartened youth. Youth “Not in Labour Force, Education and Training “(NLET) increased in India by about 3 million pa 2011-12 and 2017-18. About 100.2 million youth declared themselves as NLET during 2017-18.

Sector- wise Distribution of Employment

In this sector, sector wise distribution of employment as well as the labour force participation of the past ten years have been looked into and analysed.

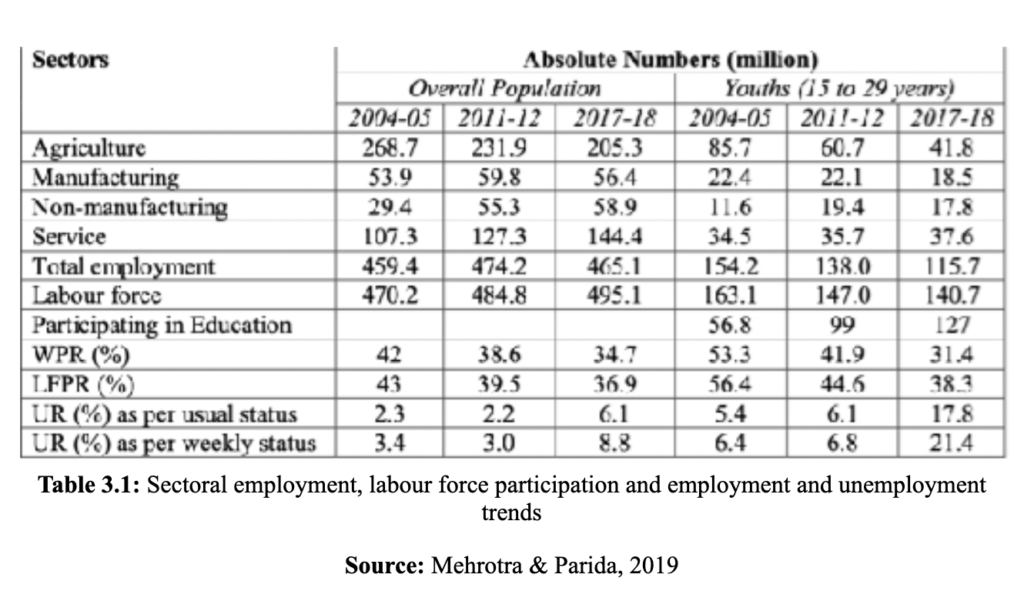

Looking into Table 3.1, a noticeable shift in employment from agriculture to the manufacturing sector and the services sector can be seen. Even though there has been a decline in employment in the agriculture sector, it still accounts for 43% of overall employment (according to the World Bank estimates in 2019). The manufacturing sector saw a decline in total employment from 2011-12 to 2017-18 while services saw an increase from 2010-11 to 2017-18. However, even though the employment in the services sector grew during this period, employment in this sector was mostly informal in nature.

In the manufacturing sector, the population dominantly works in small to medium sized firms which is more labour intensive and often requires a lower skillset. Mechanisation in the manufacturing sector has led to the demand of more skilled labour leaving most of the low skilled workers to opt to work in small and micro units. However due to demonetization, in late 2016 adversely impacted economic activity in the unorganised sector which may have been responsible for the decline in employment in the manufacturing sector. Mehrotra and Parida argue that sustaining growth in labour-intensive sub-sectors requires measures to boost domestic demand

along with the export promotion. In the non-manufacturing sector, the construction sector generates the most employment. However, post 2014 after slowing down of the economy, investments in infrastructure also reduced. This led to lower demand for labour in the construction sector as well. Coming to the organised sector, the share of total employment also fell from 34.5% to 29.5% post 2011-12 (Mehrotra & Parida, 2019).

When it comes to low-skilled workers, mechanisation of agriculture and low demand of construction work has led to a lower demand of which has increased the unemployment amongst the youth labour force.

Informality within the public and private sector

Over the past decade or so, contractualization within the formal sector has been the dominant form of employment. Here, the employees in the formal sector are employed on a contractual basis for a short term and the formal organisations evade the responsibility to provide job security to such employees as they are only employed on a temporary basis. This is seen across all formal sectors including government and public enterprises where jobs with a temporary contract have risen since 2017-18. In the manufacturing sector there was an increase of 0.5 million while in the series sector there was an increase of 4 million (Mehrotra & Parida, 2019).

Even though the labour absorption has been the highest in the services sector, the lack of decent jobs created has led to huge job insecurity. With around 90.7% of employment still being informal, formalisation of jobs remains a huge issue to address social security. However, there has been an increase in employment in the modern services which include education, research and development, health, telecommunication etc which require a higher level of education and skills. This is a positive trend and if continued could lead to more formal employment being generated.

Conclusion

It is critical for India to be able to generate employment opportunities in the non-farm sector. However, due to slow down in the structural transformation and declining jobs in the manufacturing sector along with poor quality of traditional jobs in the services sector has led to us questioning whether a revival in employment is possible or not. The government still being in denial of the actuality of the crisis is also concerning as appropriate measures haven’t been taken to address the issue.

According to a report by McKinsey & Company, to tackle the issue of unemployment, it is important that India’s GDP grows at about 8% to 8.5% in order to create 90 plus million non farm jobs. Generating quality jobs in the manufacturing and services sector is crucial to relieve India of its unemployment crisis. Government policies need to be formulated to encourage youth employment in emerging modern sectors such as health, social work, education, research and development and e-commerce which will help create jobs for educated youth and also lead to formalisation of jobs created.

References

Mehrotra, S. & Parida, J., K (2019). India’s Employment Crisis:Rising Education Levels and Falling Non-agricultural Job Growth. Azim Premji University.

Mehrotra, S. & Parida, J., K (2021). Stalled Structural Change Brings an Employment Crisis in India. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-021-00317

McKinsey & Company (2020). India’s turning point: An economic agenda to spur growth and jobs.

Kundu, A & Mohanan, P., C. (2009). Employment and Inequality outcomes in India. Jawaharlal Nehru University/Indian Statistical Service. https://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/42546020.pdf

Chand, R. & Singh, J. (2022). Workforce Changes and Employment; Some Findings from PLFS Data Series. Niti Aayog.

PIB (2022). Employment Situation in New India.

Gupta, M. & Pushkar (2019). Why India Should Worry About Its Educated, but Unemployed, Youth. The Wire.